Indigenous Empirical Plant Knowledge Meets Cannabis Science

By the Society of Cannabis Clinicians

Across the globe, people are turning to plant medicine. Some have to reconnect to this knowledge because it has been lost. And for others, it has continued to be their way of life for millennia. Despite the booming interest in cannabis worldwide, some people are limited in their ability to participate in the industry. In fact, those who have some of the strongest links to plant knowledge are being left out.

Dr. Yesid Ramirez is a Colombian biochemist and Doctor Magna Cum Laude in structural biology and drug design from the University of Würzburg in Germany. Since 2012, he has researched natural products as therapeutic agents. His work also has a social justice component. In an effort to bring indigenous communities into the fold of the cannabis landscape, Ramirez (a member of the SCC LATAM chapter) created a free, day-long intensive program at ICESI University in Cali, Colombia for groups that have been historically discriminated against.

Dr. Yesid Ramirez is a Colombian biochemist and Doctor Magna Cum Laude in structural biology and drug design from the University of Würzburg in Germany. Since 2012, he has researched natural products as therapeutic agents. His work also has a social justice component. In an effort to bring indigenous communities into the fold of the cannabis landscape, Ramirez (a member of the SCC LATAM chapter) created a free, day-long intensive program at ICESI University in Cali, Colombia for groups that have been historically discriminated against.

Thanks to the ancestral ties of indigenous communities to medicinal plants and their vast experience in cultivation, they are key players in the growing development of the cannabis industry in Colombia. The country has a unique competitive advantage in the industry due to its volcanic soil and isothermal climate. The goal of Ramirez’s course was to provide the scientific framework to enable indigenous communities to join the medical cannabis market. Sarah Russo, the SCC’s Creative Director, had a chat with Dr. Ramirez after the event. They recapped the importance of social justice advocacy, course highlights, and ways that the international community can support indigenous groups in the cannabis space.

Sarah Russo: How have indigenous groups in Colombia been discriminated against?

Dr. Yesid Ramirez: Our history started with European colonization. It was a campaign of sword and cross. People were forced to speak Spanish or were killed. There was a constant decimation of the local cultures. For example, many places of worship for indigenous communities were burned down. And churches were built upon that. For example, here in Cali the famous San Antonio church in the middle of the city was once a shrine for the Calima. Chief Petecuy and his people tried to stand against Spanish colonizers but in the end, they were displaced. Since then, the culture is completely fixated on white, European Spanish origins. Many of the families that took over the land are descended from Spanish colonizers. They now rule the economy here. There is still an idea that indigenous communities are uncultured and should be in the jungle away from the cities.

Now the indigenous communities are quite secluded. They have a way lower income because they live separate from the cities. They don’t have as much access to education and healthcare. They are generally neglected by the government. They don’t get the same rights even though they are Colombian. They don’t have the same access to education and healthcare as the descendants of colonizers do. In the culture, there is still this stigma that being indigenous is bad. This was especially visible during the protest last month. There were strikes against the government here in Colombia. Indigenous communities came to the cities to support the students in demonstrations against right-wing policies. People from the richest neighborhoods in Cali came with guns and started shooting with the aid of the police. Civilians picked up guns and were side by side with the students. Students were not considered protestors. They were considered vandals. They said that indigenous people were supporting the terrorists and so on. Many rich Colombians with guns were in the street shooting people. The severity of the situation was downplayed because they were killing “vandals” and indigenous people. There’s no pride in our heritage at all. It’s the opposite. It’s quite sad.

SR: Do you have indigenous heritage or know much about your origins?

YR: Actually, yes. I looked into my father’s family history and he’s from a town around the River Magdalena. In this area a tribe called the Pijao lived. My father is descended from them. As an international student in Germany, I was always looking at the students from Romania, Czech Republic, and Germany. They had their own language. They had their own culture. They had an identity tracing back hundreds of years. But for me, I didn’t know who my people were or what they looked like.

Earlier this year, I made a trip through the Valley of the Magdalena where indigenous communities used to inhabit. I went to many historical sites. In some of the very small towns, the kids looked exactly like my father’s side of the family. I realized my genetic origins. They have the same skin, ears, and hair as my father. Although my father does not have this culture anymore. There were many nice things that I found on this trip that shouldn’t be forgotten. There is a strong heritage for all Colombians that has nothing to do with Spanish origins. My mom’s side is of Spanish descent, so I’m a mix. Both are part of me. And I don’t think it’s correct that in Colombia we forget our whole heritage.

SR: How have ingenious communities in Colombia been left out of the cannabis industry?

YR: When the cannabis legislation started, there were many regulations. You need to get a lot of permits and jump through many bureaucratic hoops. That is understandable. Cannabis needs regulation. But to comply with the Good Manufacturing Practice and the laws, you need a lot of funding. Basically the cannabis industry is only available to people with money. This not only leaves out indigenous communities, but also everyone who’s not rich. The problem is that these people that have a lot of money think they know about cannabis, but they don’t. I think this industry will benefit a lot if we incorporate more parts of society, like researchers and universities. Indigenous communities have the practical knowledge of cannabis and other plants. Educational programs do not reach the indigenous community. This was the main motivation of the seminar that I did. They are denied knowledge and education which makes it impossible to get into business without political influence or being a millionaire. It leaves out everyone who isn’t within this circle of power.

SR: What you described is also very much the case in other countries and the historically discriminated groups living there. It seems to be a common theme, unfortunately. From your perspective, what particular ways do indigenous communities bring insight to the field of cannabis therapeutics?

YR: Medicine originated through the relationship of humans with nature. That was how everything started. Nowadays, we have very sophisticated ways to approach nature. Many doctors have forgotten this knowledge. There are actually many things we discovered through the relationship with nature, including the entourage effect.

Indigenous communities still have a connection to nature because it is their way of life. They may not have the knowledge of pharmacology and interactions with receptors and enzymes, but they know what plants to put together in order to have a therapeutic effect. We should acknowledge that as valid knowledge. There is a vast benefit to their relationship with plants. We can try to contextualize their practices in the modern medicine framework. We could analyze what is in the plant species they use, what compounds they have, how they interact with each other. We could bring in new dimensions to better be able to monitor this. For example, with ayahuasca you need to mix two plants. If you use only one of them, it doesn’t work. One of them is psychoactive and contains DMT and the other inhibits the breakdown of the compound (MAOI inhibitor). Indigenous groups didn’t know anything about the pharmacological effects of these plants. But they still found out thousands of years ago if they put them together, then you will have the effects that ayahuasca has.

This happens with many different drug preparations. Indigenous groups create plant based medicines which they say address a lot of diseases. If we try to analyze some of them and put them in the context of modern medicine, we might find very interesting pharmacological interactions that we wouldn’t have figured out otherwise. Because indigenous groups have very strong empirical knowledge that has some meaning in basic pharmacology. And because we have abandoned this empirical way of doing medicine, this is knowledge that by definition we cannot access anymore.

SR: Scientific discovery is often used to validate some of the healing properties of plant medicine used by indigenous groups. Through this, how can researchers be sure to respect and preserve their rights to use plant medicine and not exploit their culture?

YR: To preserve the rights and original knowledge of these communities, a benefit sharing agreement must be signed beforehand in in compliance with the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). This ensures that any shares made from their knowledge will be properly distributed.

SR: You gave a course recently for the indigenous communities of Colombia to help support cannabis education. What did this course focus on and how was it received by the people who participated?

YR: We started out with the history and how cannabis has been used as a medicine in Asia for millennia. I explained how ancient cultures like the Assyrians and Sumerians had a relationship with the plant. Up to the first half of the 20th century it was completely normal to walk into a pharmacy and get cannabis-based medicine. I covered why it was made illegal and the economic interests in the United States in the 1930’s that led to the criminalization of cannabis and hemp. The discovery of THC changed perspective and cannabis was recognized as a medicine again. This was to highlight that the prohibition era is an exception in the history of cannabis, not the rule. And then I explained the basic science and pharmacology of cannabis and terpenoids, what therapeutic activities they have, and how they interact together. Then we moved to the endocannabinoid system, focusing on the CB1 and CB2 receptors, but not with too much detail. But I did explain to them there was an endocannabinoid system where cannabis was acting and controlling every single physiological process in our body. Endocannabinoids are a part of us independent from the cannabis plant. So the real protagonist is not cannabis itself but our own endocannabinoid system.

Because of their relationship with ayahuasca, I explained the 5H2A receptor where DMT acts and how the CB1 receptor interacts with the psychedelic receptors so they could make the connection. And after that we discussed the accepted therapeutic uses of cannabis. I shared the report from the National Academy of Sciences and Engineering and told them the four accepted applications of cannabis that have scientific consensus. Although it can be useful for many more conditions. I explained that companies like GW Pharmaceuticals make cannabis medicine now with Epidiolex and Sativex. They have quality system management applied for the safety of the patients.

We discussed the need for reproducibility for the efficiency of the medicine and what was needed to implement such a thing. I shared a real case of a patient that came to us, an 18-year-old girl who had up to 10 epileptic attacks a day. The parents bought a cannabis formula locally that was said to be a CBD dominant preparation with small amounts of THC. The patient took it and ended up being hospitalized. So I put the product in the HPLC and I found there was no CBD, only THC. So I explained that THC can be a medicine. But if you put on the label that it has CBD, and it doesn’t, you are misleading the patient. We standardized a formula with a CBD dominant variety and now the patient is fine. It’s not only making extract from the plant, you really need to pay attention to the dose. They got a real example of what happens when you don’t standardize.

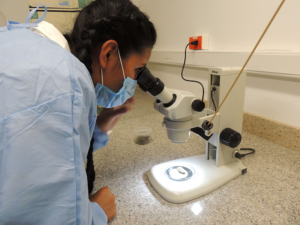

The course participants liked the discussion about their relationship with ayahuasca, but they liked thepractical part of the seminar the most. We went through the HPLC and prepared a cannabis sample for analysis. I showed them how the HPLC tests the sample and how the chromatogram can show the quantity of active compounds. They were very happy to be in their lab coats. They were taking pictures and videos. We looked at a stereoscope which had a cannabis flower where you could see the trichomes nicely. They hadn’t done that before.

SR: It sounds like they got a full experience. What can people do to support the efforts of Colombian indigenous groups in the medical cannabis landscape?

YR: The main responsibility, I think, lies with Colombians. They should vote more wisely in the future. They need to pay more attention, not only to the President, but also to Congress. We need to be more respectful of our heritage. Internationally, people could create awareness highlighting the importance of ancestral knowledge for this kind of development. The government is hesitant to admit this, although there is international pressure. Finally, I don’t know if there are organizations that support the development of the cannabis industry within indigenous communities. Some indigenous groups have their own companies and international investors. There should be organizations that help to reunite funds for companies that are owned by indigenous companies and invest in that. But again, the main responsibility remains with Colombians and our own government to open minds and finally accept our heritage. Because there are a lot of beautiful things to take advantage of.

Are you working for advocacy for indigenous communities in the cannabis sphere? If so, please contact us.

Photo and video credit: Victoria Roble

Further Information

- ICESI University Announces Free Cannabis Science Course for Members of Indigenous Communities In Colombia

- Cannabis Medicinal en Latinoamérica: del Laboratorio a la Clínica

- Dr. Yesid Ramirez Publications on Research Gate

- Dr. Ramirez Linked In

- Synergy with Cannabis and Other Herbs: Thinking Beyond Plant Constituents